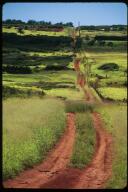

When you drift into the Methow Valley, you’re in cowboy country where cattle and horses outnumber people. The Charlie Russell landscapes are the genuine article, and, in fact, it is widely believed that Owen Wister, famed author of The Virginian, derived many of the settings and heroes of his novel from Methow Valley and Winthrop.

Today, the Methow (pronounced Met-how) Valley comprises the small towns of Mazama, Winthrop, Twisp, Carlton and Pateros with lush open country in between where fields of baled hay, pastured livestock and big old weathered barns are graced with a backdrop of the rugged Cascade Mountains.

Winthrop, one of the most popular towns in the valley, offers the facilities and services you’d expect from a major vacation center but with a strong western flavor. Strolling down the town’s wooden sidewalks, you’ll find yourself back in the 19th Century West with false-front wooden buildings, hitching rails and other western trappings. If you time it right this fall, you may witness cowboys (the real thing!) on horseback driving cattle down Winthrop’s main street, moving them from mountain summer pastures.

Mountain lodges, resorts, dude ranches, conventional motels, and bed and breakfast inns abound in Winthrop. Seventeen campgrounds located within eight miles of Winthrop include state parks, forest service campgrounds and private campgrounds. It’s a great place to shop, especially for unique gift items and western clothing. A steak dinner takes on a definite western flavor here and if you happen to be visiting on a Saturday night, you’ll have a chance to dance to the strong beat of western music.

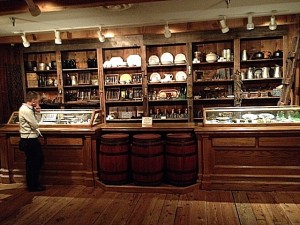

Of special interest in Winthrop is the Shafter Museum with exhibits of furniture, tools, bicycles and carriages depicting the area’s early days. Adjacent buildings feature a well-stocked old-fashioned country store and displays of old mining equipment.

For a romping, stomping good time, take in the rodeos Memorial Day weekend, May 23 & 24 and the Labor Day weekend, September 5 & 6, presented by Methow Valley Horsemen.

Twisp, like Winthrop and the other small valley towns, offers good browsing for western art and craft items made by local artisans. At the western edge of town, the U.S. Forest Service Smokejumper Base welcomes visitors during fire season, normally June through October. Parachuting firefighters in to fight forest fires began here as a national experiment in 1939.

Dozens of small lakes dot the region making the Methow and adjacent Okanogan country ideal for trout fishing. Most of the lakes have campgounds and small rustic resorts with rental boats available. The Methow River is a renown rafting destination and several outdoor companies operate regular trips. One-day or overnight horsepacking and backpacking offer a closer look at the forestlands and the spectacular Pasayten Wilderness north of Winthrop.

The Methow Valley is a great destination, rich in wild scenery and plenty of things to do. For more information, call the Winthrop Chamber of Commerce, (509) 996-2125,

or visit the Methow Valley website at www.methow.com.