From: Tubob: Two Years in West Africa with the Peace Corps

From: Tubob: Two Years in West Africa with the Peace Corps

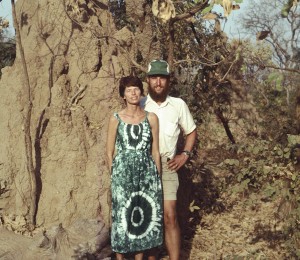

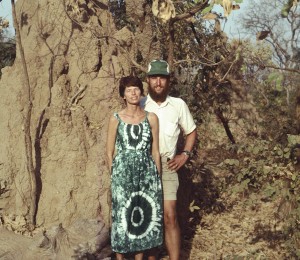

Left: Mary & Bruce standing by a termite hill.

Toward the end of our first month in The Gambia, while we were still in training, we took a three-day trip with George Scharffenberger, The Gambia’s Assistant Peace Corps Director, to what would be our assigned village, Mansajang, near the small town of Basse.

A word here about how the Peace Corps operates. Before sending a volunteer to a village, the Peace Corps first talks to the village chief, the Alkala. They determine the need and discuss the work expected of the volunteer and where he or she will live. In Bruce’s case, the UN had determined they would continue the UNICEF well-digging project and Bruce would serve as a mechanical advisor. In my case, the Health Department said they could use a health worker in the Basse area, the closest town to the village of Mansajang. So our visit at this time was expected and many of the details worked out beforehand.

We were excited to see where our future life would be. George picked us up in the Peace Corps’ small Peugeot truck. The first 120 miles were paved, but for the next 125 miles we bumped along on deeply rutted roads with potholes that could easily break a truck’s axle. It was a long, hot drive.

Along the way, we stopped at several volunteer homes so George could deliver their mail. It was interesting to see how they lived. Some lived in round grass-thatched roof huts, but most lived in row houses. These row houses, much nicer than those we saw in the capitol city of Banjul, normally housed two to four families, commonly an extended family. In most, each “apartment” had two rooms, but some only one. I found the row houses much hotter than huts with thatched roofs. Without a ceiling, heat radiates from the corrugated roofs. Some row houses, and huts too, had dirt floors; others had concrete.

We visited the working places of two volunteers, one at a clinic and one at a hospital. As it happened, the volunteers we visited were health workers.

At one point we gave two women volunteers a ride to the next village. We three filled the truck’s small cab, so they sat in the open back of the pickup. The weather had been very dry and clouds of red road dust shrouded the truck. When the two women climbed out, they were covered with red dust. They just laughed and brushed off themselves, and each other, and went on their way.

We had fun traveling with George. His quick sense of humor and his vast knowledge of West African culture impressed us and helped put us at ease. At one point he pulled off the road and pointed to a cone-shaped mound. “Do you know what that is?”

The mound looked solid, was about eight feet tall and about five feet across at its base. We hadn’t a clue.

“A termite hill. They’re as hard as concrete. I knew a fellow who died when his car plowed into one.”

After George pointed them out, we continued to see them in rural areas.

We passed many people walking with loads on their heads, the women often with babies slung on their backs. The men often stopped and waved. Hitching for a ride isn’t done with a thumb, but rather the whole arm extended with a limp hand waving up and down. We picked up two men and gave them rides to the next village.

We were thrilled with the trip. Finally, we saw African life more like what we imagined it would be: family compounds, peaceful village scenes and friendly people. Chickens, goats, sheep, cattle, horses and donkeys grazed near family compounds. Amazingly, the sheep, bred for meat, didn’t have wool coats like in America. It took us awhile to tell the difference between sheep and goats since their coats were so similar. On the road we saw monkeys in trees, swinging from branch to branch and scampering around on the ground, and even saw a troop of baboons.

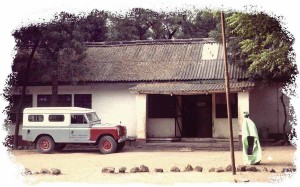

Finally, we arrived at what was known as the UN (United Nations) Compound. The currant volunteer, Howard, whom Bruce would replace, happened to be downriver at Yundum overseeing equipment repairs, so we pretty much had the place to ourselves.

We would live in two structures. One, an oblong mud-brick building, about 10 feet wide and 30 feet long, with a corrugated tin roof, had been built by Howard’s predecessor and had three small rooms, one used for cooking, the middle as a dining-living room and the third as a spare bedroom. One of the drawbacks of this structure was that flying insects could easily enter in the space between the top of the wall and the corrugated roof. Just a few steps away stood the second structure, a traditional round hut.

Because travel at night was difficult, UN people coming and going from Banjul to Mansajang needed to have a place to spend the night, so they slept in the oblong house which was already equipped with a bed covered with a mosquito net.

Howard used the round hut as a bedroom, as would we. The large round hut, about twenty feet across, had double-wall construction with perhaps four feet of space between walls, two fully screened doors, and was topped with a cone-shaped grass-thatched roof. We loved the arrangement. Actually, we probably had the best volunteer housing in The Gambia.

Besides our two structures, there were three other huts. A UN project mechanic and his family lived one. The other two were empty but often temporarily housed UN drivers who needed a place to stay for the night. None of the structures in the compound were painted or whitewashed, but were all made of mud-brick smoothed over with a thin layer of concrete.

Everyone in the compound shared one latrine. About one hundred feet from our hut, the latrine had been dug as a practice well. A deep concrete-lined hole, it was actually quite nice by local standards. The few latrines I’d used had dirt surrounding the hole. No outhouse, but krinting, the fencing commonly used consisting of coarsely woven reeds, provided privacy. Naturally, upon arrival, my first stop was to the latrine. One simply squats over the hole, and when I did perhaps 200 flies buzzed out of the hole, banging against me. I shuddered and wondered if I’d ever get used to that.

Krinting also surrounded the entire compound, as in other compounds we’d seen. The fencing provided privacy but its real purpose was to keep roving stock, cattle, sheep and goats, out. Chickens wandered about and I saw no chicken coops. A few sparse patches of grass poked through the sandy soil.

We walked to Bruce’s shop a short distance away, and met a few of the crew who weren’t downriver working on equipment. George left Bruce with them and took me to the home of Sister Roberts, my future boss. After greetings and introductions, George left to visit friends.

I immediately liked Sister Roberts, who was not a Gambian, but from Sierra Leone. The “Sister” title, the equivalent of Registered Nurse (RN), was the result of her training in England. She spoke beautiful English. I would learn more about the details of my job later, but she made it very clear she wanted me to take over record keeping. “Other than that, Mariama, you should do what you want to do. There’s plenty of work.” It felt good to be welcomed and have something solid to work toward.

Bruce didn’t come away with that feeling, however. No one he talked to at the shop seemed to have a grasp of the situation. Those who were knowledgeable were no doubt downriver at Yundum.

This worthwhile upriver trip gave us many insights so that we could prepare with confidence for when it was time to live there.

To Make a Comment: Click on “Leave a Reply.”

When she was three years old, Ginny Nugent’s mother died, and so did her loving home. Cholama Moon by Anne Schroeder tells Ginny’s story in this late 1800’s novel which takes place in a remote section of southeastern Monterey County, California.

When she was three years old, Ginny Nugent’s mother died, and so did her loving home. Cholama Moon by Anne Schroeder tells Ginny’s story in this late 1800’s novel which takes place in a remote section of southeastern Monterey County, California.