From: TUBOB: Two Years in West Africa with the Peace Corps

From: TUBOB: Two Years in West Africa with the Peace Corps

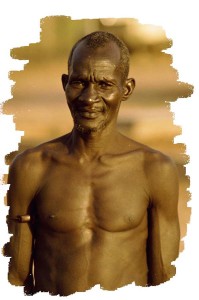

Waves of 100-degree heat shimmered off the rice fields as I walked the two miles to market. Carrying my small back pack, a few recycled plastic bags, a quart-size porcelain bowl, and a small glass jar, I slowly passed a tired donkey plodding along, his head hung low, as he pulled a heavy cart loaded with sacks of millet. With each step I took, puffs of red dust settled on my legs and sandaled feet.

Market day in West Africa is a far cry from a quick run to Safeway in Seattle. It’s an adventure.

As Peace Corps volunteers serving in The Gambia, a small West African country, my husband Bruce and I lived as our hosts lived. We hauled our own water from the well, swept our mud-brick hut with a short locally-made straw broom, cooked our own meals, and bought our supplies at the open market and small stores. We didn’t have personal transportation, so we did as the local people and walked every place we went.

I heard my name called as I trudged along.

“Mariama! Salaam Malekum!” The name, Mariama, is the African version of my real name, Mary. The traditional Arabic greeting, Salaam Malekum, is heard throughout West Africa. It means “May peace be with you.”

“Malekum Salaam, Naba,” I answered the friendly African woman. She fell in step with me and we conversed in Mandinka, one of five local languages and the one Bruce and I learned during Peace Corps training.

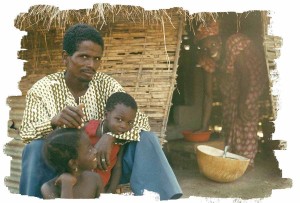

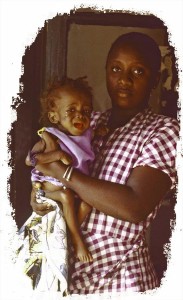

I found Gambian women to be extraordinary. Their lives were not easy–they worked hard under very difficult conditions. Their strong bodies and graceful bearing impressed me. Typically, Naba carried a baby straddled across her back. Her wide-awake little son observed his world while held close to his mother’s warm body. When he became hungry, the woman simply switched him around to her breast. At the market, Naba and I parted, each to her own errands.

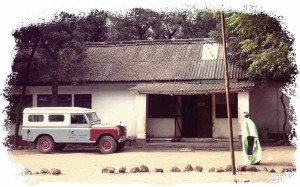

I’ll go to the meat market first, I decided with dread. The butcher’s shop, a small mud-brick building with a corrugated tin roof, was somewhat removed from the regular market. A large concrete counter separated the butcher from his customers. Goat, sheep, and beef carcasses hung from the ceiling. I tried to ignore the dead-animal smell.

The meat market crowd pushed their way to the counter. I, too, elbowed my way through the crowd. Whack! A hunk of beef fell off the carcass, severed with a mighty machete blow. Splat! Bits of meat and bone splattered on my dress and neck. Cringing, I held fast to my hard-fought place. Several flies left the main event, the beef carcass, and landed on me.

The butcher spoke a little English. “What you want?”

“Biff stek, please,” I answered. In The Gambia, previously a British-held colony, many words sound English but are pronounced with a local dialect. Whacking off a piece of meat for me, he placed it in my porcelain bowl. Then, as a treat, he dropped in a little pile of wrinkled tripe (cow’s stomach). Trying to show gratitude, I smiled, but knew I wouldn’t eat it, but I’d give it to our neighbor. As I left the meat market, my personal flies came too. I considered the benefits of becoming a vegetarian.

Fragrances bombarded me as I entered the main market, a large open-sided structure. Spices, sold by the bulk, were lined up in little bins. Large flat baskets displayed fresh roasted peanuts. The peanut vendor tore a scrap of paper–any type of paper–and folded a little package to hold the peanuts, still warm from an earthen oven. We briefly haggled over the price, an expected exchange, and I dropped the equivalent of a dime into his hand.

A baker sold piles of fresh baguettes. The earthy aroma of yeast permeated the air. Pankettas, flat yeast dough deep-fried in palm oil, quickly disappeared, breakfast for many shoppers.

I skirted around unpleasant smelling, fly-covered dried fish. We never bought it, though we’d eaten it in Gambian cooking and found it tasted as bad as it smelled. The fresh fish was lovely though and the catfish appeared to still be breathing. Anything that’s still breathing must be fresh. I bought a catfish, slipping it into one of my plastic bags.

Chickens roamed freely, pecking at the ground. Some weren’t so lucky and hung upside down, feet tied to a rod. They never seemed to struggle, awaiting their fate. As I shopped, I saw many women carrying live chickens in the crook of their arms as they conducted their shopping business.

Noise rose to an astonishing level when a bush taxi’s horn beeped as riders were dropped off. Donkeys brayed as they arrived with their heavy loads. Gambians often talked in a loud boisterous manner and now they shouted to be heard. Children darted about, squealing with their games.

Treadle sewing machines click-clacked in the background. There were no ready-made clothing shops in the village where we lived. When the need arose for a new dress or shirt, one bought the material and described to the tailor the style desired. Because of the heat, clothing was generally loose-fitting so exact measurements weren’t required, but these skillful tailors created an amazing variety of garments on their treadle machines.

I eagerly learned what vegetables were available that day. With no cold storage, the availability of most vegetables depended on the season. Tomatoes were available five months of the year, lettuce only about two months. One of our favorite vegetables, okra, was sold about nine months of the year. All year long squash was available as well as imported onions and potatoes.

Friendly women called my name, urging me to come to their attractive displays and buy the vegetables they had grown. Some men sold items too, usually businessmen who bought imported food to sell at the market.

Approaching one of my regular vendors, I admired her tomato display. Most fruits and vegetables sold by the pile, not by the pound. Each pile of five tomatoes displayed a similar assortment, perhaps one large, two medium, and two small tomatoes, in various stages of ripeness. One selects an entire pile, not one from this pile, one from that. I purchased two piles and a piece of squash.

A large rat streaked by my sandaled feet with a cat hot on its trail. Cats fend for themselves so catching that rat was serious business.

I spotted oranges, also arranged in piles of five. Although ripe, the oranges were green. Their tough skins required a sharp knife to peel. Once I counted fifty-two seeds in a single orange.

I remembered I needed rice and crossed to the other side of the market where a vendor sat next to a burlap bag. The man measured rice into my plastic bag, using a tomato paste can as his measuring device. Rice was grown locally, thanks to the Chinese who taught Gambians to cultivate this essential product. It was good rice but didn’t keep well. After a week or so it turned wormy and then it became chicken fodder. Our chickens loved it.

I needed flour. A warning stenciled on the side of the 50-pound flour sack read, “This is a gift from the United States of America. Not to be sold.” I purchased two scoops and moved on.

I had the feeling of being watched. Now I looked around quickly and sure enough, there she was, peeking out from behind a post. It was a game we played, the peanut-butter lady and I. Either she would sneak up on me, or I tried to come up behind her. We giggled like little girls at our joke. This delightful, tiny woman, beamed a huge smile showing beautiful white teeth. Her family grew peanuts and stored them for use during the year. Before going to market, she pressed fresh-roasted peanuts into a paste.

There was nothing more delicious than this fresh peanut butter, which they called peanut paste. Gambians prepare a sauce with it, called domoda, adding tomato paste and perhaps a bit of meat, spiced with hot peppers, and served on rice. Scrumptious! They couldn’t believe we spread peanut paste on bread, nor could they believe how much we bought! I held out my jar into which she plopped five two-inch balls, plus one more as a gift.

The market loomed bigger than life. The smells, noise, heat, and activity, seemed

to be the essence of these people. I considered the market to be The Gambia boiled down to the essentials. One struggled to conduct business, haggling over prices, jostling crowds, suffering with the heat and flies, but this ritual highlighted my week. While buying provisions, I’d visited with friends and shared with them their ancient marketing tradition.