Note: The following is taken in part from my memoir, Sailing with Impunity: Adventure in the South Pacific.

Operating a boat safely isn’t as easy as it might look. Before we embarked on our 13,000- mile journey aboard our Bristol 40, Impunity, Bruce insisted I take Coast Guard Auxiliary boating safety courses. I took several series of classes on boating safety, sailing skills, seamanship, and shoreline navigation. In addition, we had reference guides and nearly 200 charts on board.

Many books have been written on navigation rules of the road, and the reason for it all is safety. On the water, there are no visible traffic signals or lanes to use as guides. When you come upon another vessel, who has the right of way? How can you tell?

Like any specialty, the boating world has its own terminology. Such common words as right, left, front of a boat, back of a boat have nautical terminology (starboard, port, bow, stern). Even something as common as rope has another name: line. I could go on and on: a ceiling is overhead; wall is bulkhead, closet is locker, windows are port lights. There’s no sense arguing about it, it just is. Ocean travel is another world and if you’re going to be a part of it, you need to know the language.

Navigation rules to be observed:

●The first rule is to always have a proper lookout, someone on watch. We maintained a 24-hour watch system of 4-hours on, 4-hours off. That meant that at sea we never got more than 4 hours sleep. It also meant that our boat was in safe hands at all times.

● Boaters must have the ability to determine risk of collision. Use everything you’ve got: eyes, ears, radar, radio.

● Know how to read ships lights for night time visibility.

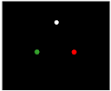

– Different types of ships— tugboat, fishing boat, cargo vessels, sailboats— have different light configurations. Aboard Impunity we had a handy chart we used for quick reference when we didn’t recognize another boat’s light configuration. Lights determine the type of vessel.

● International rules dictate that when underway all vessels must display prescribed lights.

– All boats must have sidelights: a green light on the starboard side; a red light on the port side.

– All boats must have a sternlight.

– All power boats and sailboats over 65-feet must have a masthead light, or lights, depending on the type of boat, placed over the center of the vessel.

● Know how to determine which direction a ship is sailing

– If you see a green light, the ship is passing from port to starboard (left to right).

– If you see a red light, the ship is passing from starboard to port (right to left).

– If you see both green and red lights, the ship is coming toward you and you are likely on a collision course.

– If you see only a white sternlight, the ship is sailing away from you.

There are many more “light” rules for various types of boats, but these are the basics that every boater should know.

● Know responsibilities between vessels and which vessel must give-way in an approach situation

– Learn the duties of the “burdened” (or give-way) vessel

– Learn the duties of the “privileged” (or stand-on) vessel

● Learn what to do when approaching buoys and markers

If you don’t know the rules of the road, you’re putting yourself and other vessels in danger. Knowing and following the Rules of the Road is not difficult. It is smart, courteous, and safe. And it’s the law.