From: Tubob: Two Years in West Africa with the Peace Corps

From: Tubob: Two Years in West Africa with the Peace Corps

We needed chickens to supplement our protein. I had seen live chickens for sale at the market, but when I talked to Binta, the woman in our compound, I learned these chickens were past laying eggs and sold for meat. She apparently told her husband Mosalif that we wanted chickens.

The next morning when Mosalif came to our door to greet us, he asked if we wanted him to buy chickens. Work that day would take him into the bush and he could buy young hens for us. I asked how much money he needed and gave him money enough to buy four.

Unfortunately, Bruce needed to meet with the UN project lead in Yundum and would be gone for two days. But knowing that we would be getting chickens, he had fixed up the other outside passageway of our hut as a chicken coop. Africans didn’t coop up their chickens since they didn’t eat eggs and had no need to gather them. Besides, they reasoned, why eat an egg when, left alone, it would grow into a whole chicken. Binta’s chickens roosted wherever they found a safe place, often in one of the empty compound huts or on a tree branch. Since we didn’t care to have an egg hunt every day, we needed to confine our chickens for at least the night and part of the day.

Bruce cobbled together a gate to keep them in. We found straw for them to make their nests. To begin with, we could feed them rice that had already turned buggy. While downriver Bruce planned to buy real chicken food, a by-product from peanuts. We began grinding up egg shells to mix with their food so that the extra calcium would ensure stronger shells.

At the end of the day, Mosalif stopped by with four young chickens, two of which he said would give us eggs right away, the other two would produce soon. I was thrilled.

Only having had dogs and cats, I worried that the chickens would run off, maybe join Binta’s brood. To make sure they knew where they lived, I tied strings to one leg of each of the four chickens, long enough for them to get to a nest, drink water and eat rice. My intention was to only do this for one day, until they were used to their surroundings.

On that first day Mosalif came over in the early evening to see how I was doing with the chickens. When he saw the strings, he knelt down to get a closer look. Mosalif was Fula and since I didn’t know that language, he and I conversed only in Mandinka. “A mong beteata.” This is not good, he said, watching the chickens trying to walk around, lifting the tied leg high, giving them a strange gate.

“I am afraid they’ll run away.”

He looked somber, but in thinking about it afterwards, I’m sure it was all he could do to keep a straight face. “You have fed them, Mariama. They won’t run away.” He carefully removed the strings. “When it is dark, they will come back to this place. Then you close the gate.”

Well, I wasn’t at all sure about that, but I’d give it a try. Sure enough, at dusk they all filed into the chicken coop as though they’d done it all their lives. I closed the gate behind them.

During our stay in The Gambia, we derived great pleasure, entertainment and nourishment from our chickens. We were the only volunteers in-country with chickens and I marveled at that. Once a week we enjoyed an egg dinner, usually an omelette, and eggs for breakfast once or twice a week, plus I used eggs in puddings and other desserts. I found I could make a double boiler by inserting my covered enamel bowl into my large pot filled with water and prepare a very good cheese souffle or a delicious bread pudding, both dishes using four eggs.

Even though there were plenty of nests, two or three chickens often crammed into one nest, African style, like people on bus seats. Our flock grew, some we bought, many were given to us. At the most we had seventeen chickens.

We named our chickens, names that seemed to fit their little personalities: Ruth Schultz, Blue, Kunta Kinte, Myrtle and Penny, who was the color of a copper penny, and two that we called Sisters because we got them at the same time and couldn’t tell them apart.

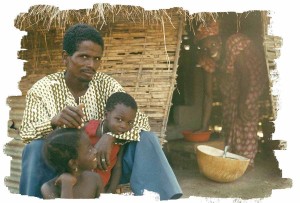

While in the Peace Corps, I frequently went on trek, sometimes with Sainabou or another auxiliary nurse, sometimes alone. An orderly/driver took me from the Basse Health Center to a distant village where a family lived whose child had been hospitalized. I wanted to call on the family to see how the child was doing and perhaps offer nutrition counseling.

While in the Peace Corps, I frequently went on trek, sometimes with Sainabou or another auxiliary nurse, sometimes alone. An orderly/driver took me from the Basse Health Center to a distant village where a family lived whose child had been hospitalized. I wanted to call on the family to see how the child was doing and perhaps offer nutrition counseling.